One practical use-case for using large language models in network operations is to help query large datasets of network telemetry faster and more easily by using natural language. This can improve NetOps and facilitate better data-driven insights for engineers and business leaders. However, the volume and nature of the data types we commonly utilize in networking makes this a daunting workflow to build, hence the dichotomy of build vs. buy.

There are network vendors building natural language query tools for network telemetry, and so it’s important to understand the value, components, and fundamental workflow whether you’re researching vendors or building your own proof of concept.

A reasonable approach, even just to experiment, is to start very simple, such as querying only one data type. That way, we can ensure accuracy and see meaningful results right away. In time, we can build on this initial workflow to include more types of data, perform more advanced analytics, and automate tasks.

Types of network telemetry

We can break down the data types we normally deal with in IT operations networking into two high level categories – structured and unstructured.

Structured Data

Structured data is highly organized, typically stored in relational databases with predefined schemas, and easily queried using tools like SQL or Python libraries such as pandas. It’s typically pretty consistent and can be queried with relatively straightforward workflows.

Structured network telemetry includes device metrics like interface stats, CPU utilization, temperature, and so on. Flow records also have clean and defined categories like source IP address, protocol, bytes transferred, and many others. Routing tables and SNMP traps are also examples of structured network data, and so are event logs with timestamps to extent, since they sort of blend both structured and unstructured elements.

Unstructured Data

Conversely, unstructured data lacks a meaningful organizational framework or data model. Because of this, unstructured data is more difficult to organize and query. Unstructured data is usually some form of text, image, audio, or video. But often what we call unstructured might be a kind of semi-structured data, such as JSON and XML.

Examples of unstructured network telemetry data would be device configuration files, vendor documentation, network diagrams, internal documentation, emails, tickets, TAC phone call recordings, and so on. LLMs can make querying unstructured data like all your old tickets (text) much easier and therefore more helpful since LLMs are semantic frameworks designed to deal with language.

Both structured and unstructured information are critical to running a network, so a these two approaches complement each other. But to keep things simple, starting with only one type of data, in this case a structured data type such as flow logs, is a great way to experiment and see meaningful results right away.

How an LLM can help query structured data

An LLM can take our natural language prompt and almost instantly translate it into the relevant query syntax. As part of a greater workflow, the generated query can run programmatically without intervention and return the data we want.

Because I’m focusing on structured data, there’s no real need to use a vector database in a RAG system because vector databases are primarily used for unstructured semantic search. Querying structured data like flow records or metrics doesn’t require semantic similarity. Yes, the LLM itself relies on semantic similarity to understand our prompt and generate the query, but that’s built into the model, not our database of structured network telemetry data.

Hybrid use cases

Another approach is to use both methods. In a hybrid approach, you could use a RAG system with a vector database to retrieve relevant unstructured context (e.g., logs explaining an anomaly or known issues), and then have the LLM generate a precise SQL or Python+pandas query to your flow database to pull matching records or do an analysis.

This would require a more complex workflow, but in this way you can make use of both the valuable unstructured data in your logs, tickets, and documentation alongside the hard numbers we get from structured data from device metrics and flow logs.

Querying flow records

I started with flow records since they’re easy to work with and contain so much interesting information. Instead of generating flows from my ContainerLab environment, I downloaded several flow datasets published by the University of Queensland. Flow data is nice to use for this type of experiment because (depending on the records) there are usually many columns of information which means you can prompt the LLM with a nice variety of queries.

For testing, there’s no need to use a large database. For this exercise, I used a small dataset of around 442 MB containing about 2.4 million rows and 43 columns.

Setup

You don’t need much for this to work. I used an old Poweredge R710 with 2 TB of storage and 64 GB memory. I normally use this to run a ContainerLab environment, some Ubuntu hosts, and a few virtual devices like a Cisco vWLC. For this test, I spun up a fresh install of Ubuntu 24.1 with 24 GB memory and 50 GB storage.

On this host I ran Ollama 1.5.7 and installed several LLMs including different versions (parameter size) of Llama 3.1, 3.2, and 3.3. I also experimented with Mistral. Llama 3.3 was noticeably slower, even with the smaller dataset.

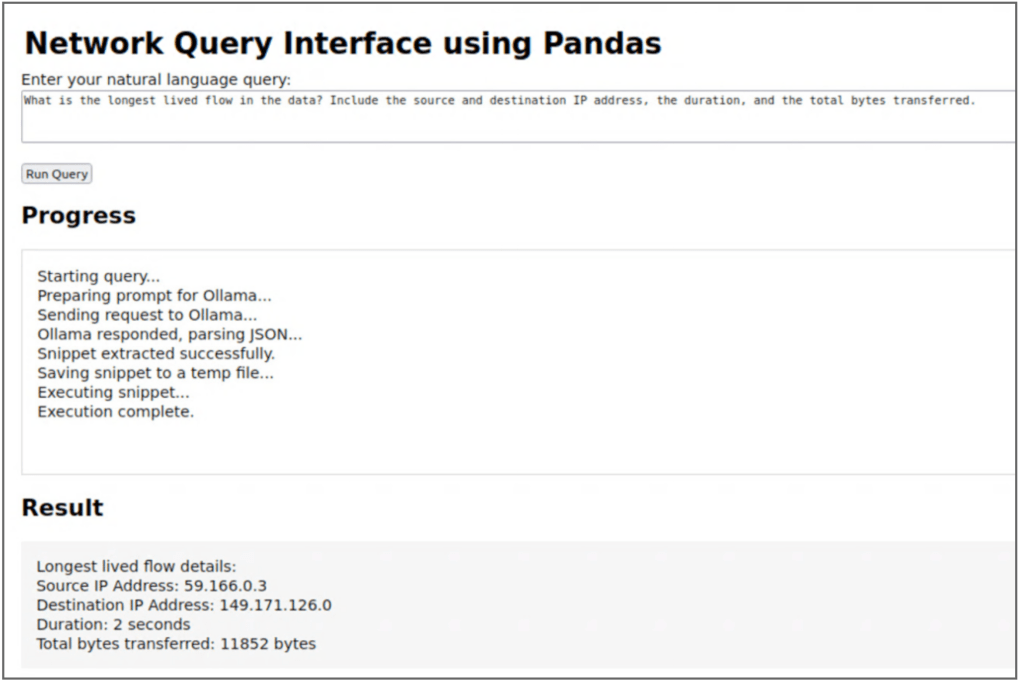

Using an LLM to generate a pandas operation

First, I used various versions of Llama to generate a pandas operation. Though this is both effective and relatively straightforward, it requires loading the entire CSV every time which makes the query slow (queries took about 3-4 minutes to return a result). But my goal was to see how accurate the results would be and what the workflow would look like, so that was fine. Since the dataset is a CSV, I was able to look up the answer manually to confirm if the LLM returned the correct answer (or not).

I added all the fields in the CSV in the function generate the code, and I set the temperature to 0.2 since there’s no need to add randomness to the result. Below is a snippet of the code to generate the query.

def send_progress(msg):

"""Put a progress message into the queue."""

progress_queue.put(msg)

def get_code_snippet_from_ollama(natural_query):

"""Use Ollama to get code snippet, with progress updates."""

send_progress("Preparing prompt for Ollama...")

prompt = f"""

You have a CSV file at: {CSV_PATH}.

The CSV has these columns: IPV4_SRC_ADDR, L4_SRC_PORT, IPV4_DST_ADDR, L4_DST_PORT,

PROTOCOL, L7_PROTO, IN_BYTES, IN_PKTS, OUT_BYTES, OUT_PKTS,

TCP_FLAGS, CLIENT_TCP_FLAGS, SERVER_TCP_FLAGS,

FLOW_DURATION_MILLISECONDS, DURATION_IN, DURATION_OUT, MIN_TTL,

MAX_TTL, LONGEST_FLOW_PKT, SHORTEST_FLOW_PKT, MIN_IP_PKT_LEN,

MAX_IP_PKT_LEN, SRC_TO_DST_SECOND_BYTES, DST_TO_SRC_SECOND_BYTES,

RETRANSMITTED_IN_BYTES, RETRANSMITTED_IN_PKTS,

RETRANSMITTED_OUT_BYTES, RETRANSMITTED_OUT_PKTS,

SRC_TO_DST_AVG_THROUGHPUT, DST_TO_SRC_AVG_THROUGHPUT,

NUM_PKTS_UP_TO_128_BYTES, NUM_PKTS_128_TO_256_BYTES,

NUM_PKTS_256_TO_512_BYTES, NUM_PKTS_512_TO_1024_BYTES,

NUM_PKTS_1024_TO_1514_BYTES, TCP_WIN_MAX_IN, TCP_WIN_MAX_OUT,

ICMP_TYPE, ICMP_IPV4_TYPE, DNS_QUERY_ID, DNS_QUERY_TYPE,

DNS_TTL_ANSWER, FTP_COMMAND_RET_CODE, Label, Attack.

Write valid Python code using pandas to answer the following query:

'{natural_query}'

Return only the code, wrapped in triple backticks if needed.

"""

payload = {

"prompt": prompt,

"system": "You are a helpful assistant that outputs ONLY Python code in the 'response' field.",

"model": MODEL_NAME,

"stream": False,

"temperature": 0.2

}

send_progress("Sending request to Ollama...")

resp = requests.post(OLLAMA_URL, json=payload)

resp.raise_for_status()

send_progress("Ollama responded, parsing JSON...")

resp_json = resp.json()

# Log the raw response

raw_response = resp_json.get("response", "").strip()

send_progress(f"Raw LLM Response:\n{raw_response}")

# Extract code snippet and remove backticks

code_snippet = re.sub(r"^```[a-zA-Z]*\n?", "", raw_response)

code_snippet = re.sub(r"```$", "", code_snippet.strip())

if not code_snippet:

send_progress("Error: No code snippet returned by Ollama.")

raise ValueError("The LLM did not return a valid pandas operation.")

send_progress(f"Generated Pandas Code:\n{code_snippet}")

return code_snippet

def run_snippet(code_snippet):

"""Write snippet to temp file, run it, return output, with progress updates."""

send_progress("Saving snippet to a temp file...")

with open(TEMP_PY_FILE, "w") as f:

f.write(code_snippet)

send_progress("Executing snippet...")

result = subprocess.run(["python3", TEMP_PY_FILE], capture_output=True, text=True)

send_progress("Execution complete.")

stdout = result.stdout

stderr = result.stderr

output = ""

if stdout:

output += stdout

if stderr:

output += f"\nErrors:\n{stderr}"

return output.strip()

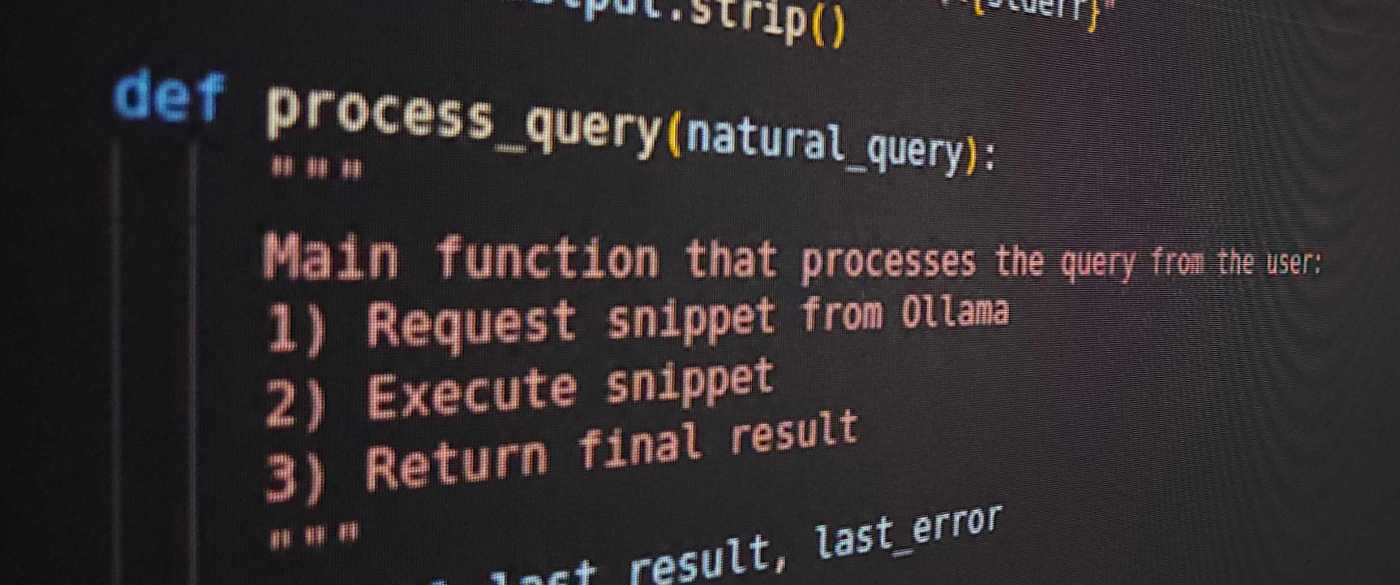

def process_query(natural_query):

"""

Main function that processes the query from the user:

1) Request snippet from Ollama

2) Execute snippet

3) Return final result

"""

global last_result, last_error

last_result = None

last_error = None

try:

code_snippet = get_code_snippet_from_ollama(natural_query)

result = run_snippet(code_snippet)

last_result = result

except Exception as ex:

last_error = str(ex)

send_progress(f"Error: {last_error}")

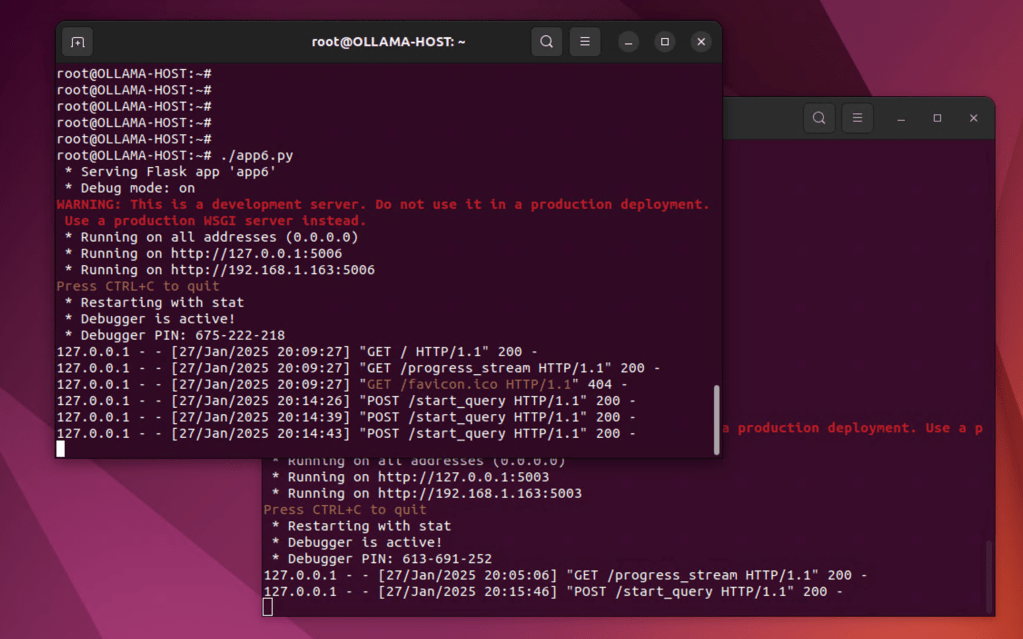

I also created a flask app for a simple web interface. I think it came out pretty good for a former network engineer who has to google his way through almost every single line of code. I also added a progress section so I could track activity, and in the subsequent iterations I made that more or less verbose.

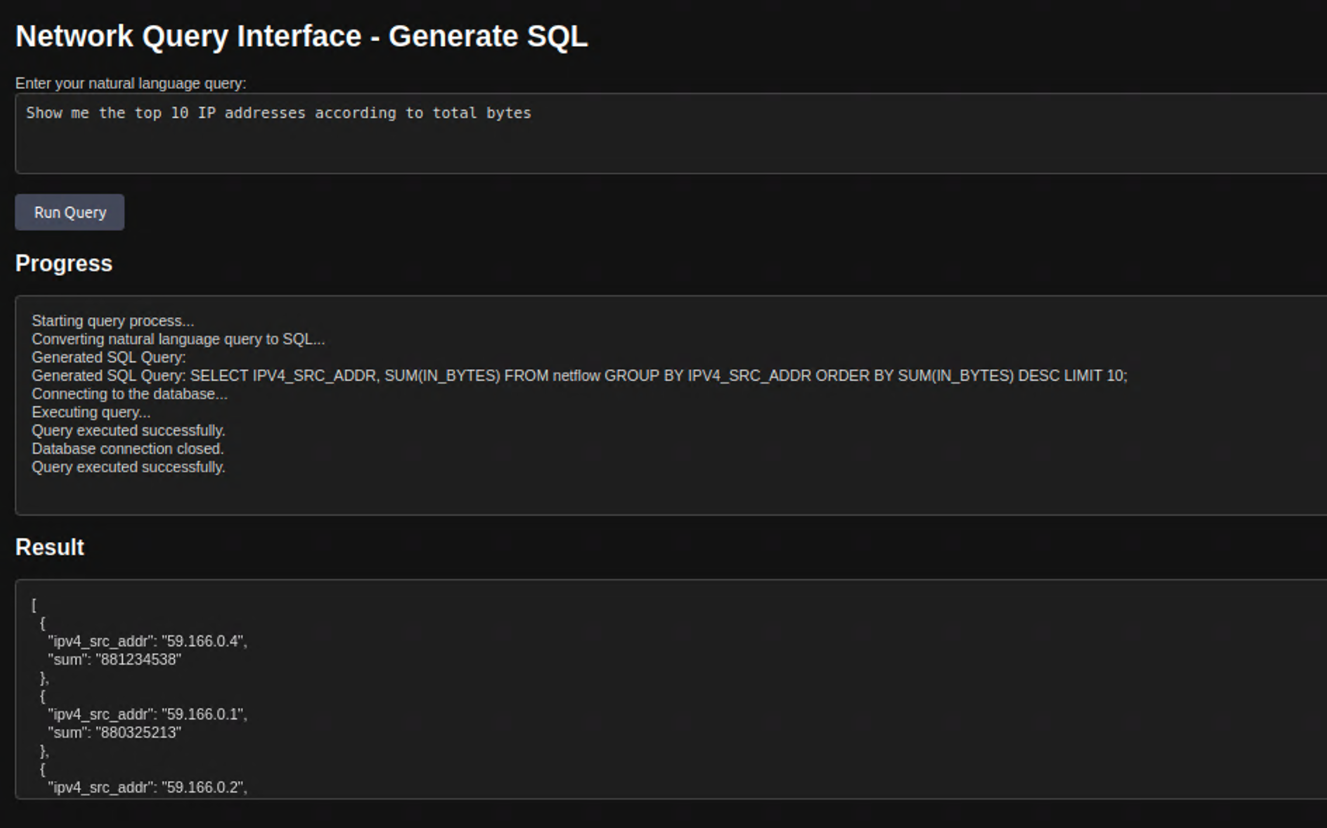

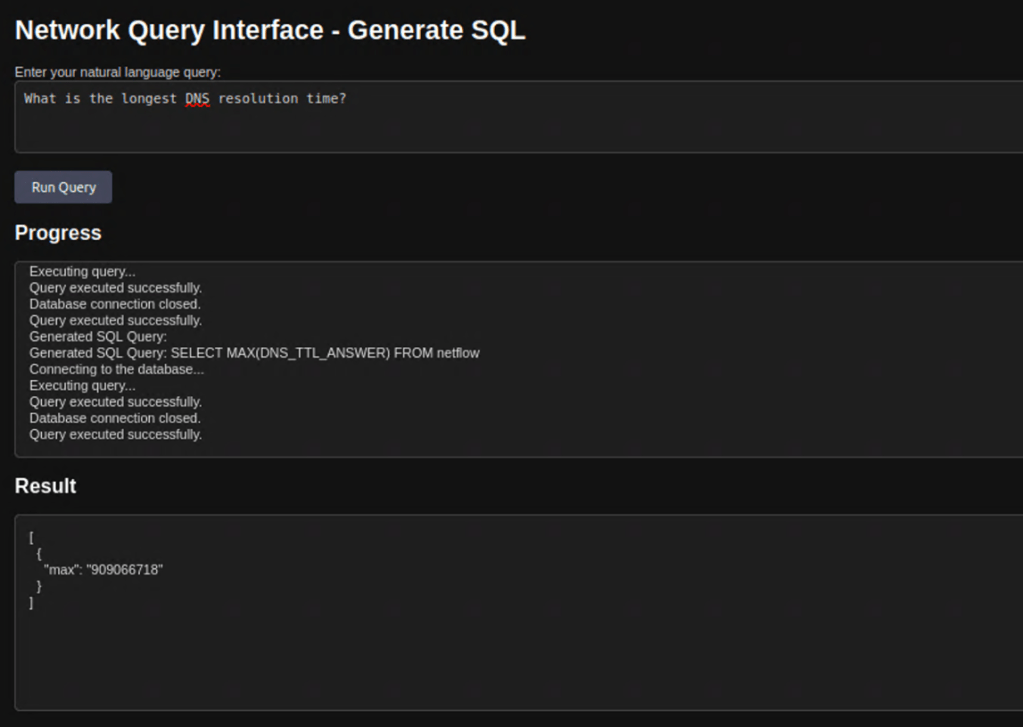

Using an LLM to generate a SQL query

Using that CSV, I also created a PostegreSQL database and ran the same query by generating SQL. This was noticeably faster. I experimented with various prompts to see how it would generate the query syntax. The next code snippet shows a few of the functions to generate the query and progress notifications.

def send_progress(msg):

"""Put a progress message into the queue."""

progress_queue.put(msg)

def convert_nl_to_sql(natural_query):

"""Convert a natural language query to SQL using Ollama."""

send_progress("Converting natural language query to SQL...")

try:

prompt = f"""

You are a database assistant. Convert the following natural language query into a valid SQL SELECT query for the database with the following schema:

- Table: netflow

- Columns: IPV4_SRC_ADDR, L4_SRC_PORT, IPV4_DST_ADDR, L4_DST_PORT, PROTOCOL, L7_PROTO, IN_BYTES, IN_PKTS, OUT_BYTES, OUT_PKTS, TCP_FLAGS, CLIENT_TCP_FLAGS, SERVER_TCP_FLAGS, FLOW_DURATION_MILLISECONDS, DURATION_IN, DURATION_OUT, MIN_TTL, MAX_TTL, LONGEST_FLOW_PKT, SHORTEST_FLOW_PKT, MIN_IP_PKT_LEN, MAX_IP_PKT_LEN, SRC_TO_DST_SECOND_BYTES, DST_TO_SRC_SECOND_BYTES, RETRANSMITTED_IN_BYTES, RETRANSMITTED_IN_PKTS, RETRANSMITTED_OUT_BYTES, RETRANSMITTED_OUT_PKTS, SRC_TO_DST_AVG_THROUGHPUT, DST_TO_SRC_AVG_THROUGHPUT, NUM_PKTS_UP_TO_128_BYTES, NUM_PKTS_128_TO_256_BYTES, NUM_PKTS_256_TO_512_BYTES, NUM_PKTS_512_TO_1024_BYTES, NUM_PKTS_1024_TO_1514_BYTES, TCP_WIN_MAX_IN, TCP_WIN_MAX_OUT, ICMP_TYPE, ICMP_IPV4_TYPE, DNS_QUERY_ID, DNS_QUERY_TYPE, DNS_TTL_ANSWER, FTP_COMMAND_RET_CODE, Label, Attack.

Natural language query: "{natural_query}"

Return only the SQL query with no explanation, comments, or additional text.

"""

payload = {

"prompt": prompt,

"model": MODEL_NAME,

"stream": False

}

response = requests.post(OLLAMA_URL, json=payload)

response.raise_for_status()

result = response.json()

# Extract the response field and validate the SQL query

sql_query = result.get("response", "").strip()

if not sql_query.lower().startswith("select"):

raise ValueError(f"Generated query is not a valid SELECT statement: {sql_query}")

send_progress(f"Generated SQL Query:\n{sql_query}")

return sql_query

except Exception as e:

send_progress(f"Error during SQL generation: {e}")

raise

def execute_sql_query(query):

"""

Execute a SQL query on the PostgreSQL database.

:param query: SQL query string.

:return: Query result as a list of tuples.

"""

send_progress("Connecting to the database...")

conn = None

result = []

try:

conn = psycopg2.connect(**DB_CONFIG)

send_progress("Executing query...")

with conn.cursor() as cur:

cur.execute(query)

result = cur.fetchall()

send_progress("Query executed successfully.")

except Exception as e:

send_progress(f"Error: {e}")

raise

finally:

if conn:

conn.close()

send_progress("Database connection closed.")

return result

Testing Models

I did the same with smaller versions of Llama 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, and Mistral 7B. Llama 3.2 gave me the most consistent results (which was surprising to me), but this wasn’t a very controlled or elaborate experiment, so take that with a grain of salt.

I chose to use only open source, so I didn’t try GPT or Claude. Here’s an example of a result that was incorrect, which was really strange to me because this one was using the latest Llama 3.3.

Conclusion

Even with under-powered lab computers, it’s still pretty fast to query databases of flow records this way, with SQL being faster than a pandas operation. I really do have to google a lot of the code I write, so using an LLM to enable me to query data like this was really amazing.

I found that the more complex my prompt, the greater the incidence of the model generating a query that wasn’t exactly what I was looking for. This tells me we’re still relying on the ability of the LLM to correctly translate our natural language into the relevant syntax. Trying different prompts to get the same information gave me mixed results.

Next I’d like to add a second small database of metrics and see how the LLM handles generating a SELECT query to fetch data from multiple tables rather than using joins ahead of time. Really where I’m going is a hybrid approach using a workflow to decide how to route prompts. That way I can query both structured and unstructured network data in the same query tool.

I have some ideas for that, and of course I’m scouring blogs, Hugging Face, and YouTube to see what people are doing.

Thanks,

Phil

Leave a comment